Introduction

When you walk onto the processing floor of a factory like JADE MAGO, the first thing that hits you is the sound of diamond saws slicing through solid rock, followed by the distinctive hum of high-speed polishing wheels. For decades, my team and I have stood amidst the dust and slurry, transforming rough boulders into exquisite pieces of art. In our industry, we often hear clients ask a fundamental question: “What actually counts as a semi-precious stone?” To the average consumer, it might be a question of price, but to us manufacturers, it is a question of hardness, availability, and processing complexity.

The term “semi-precious” is ubiquitous in the jewelry trade, yet it is often misunderstood or dismissed as a label for “lesser” materials. However, in the vast ecosystem of Chinese stone processing, these materials represent the bulk of global trade and artistic innovation. From the translucent depths of high-grade agate to the spiritual resonance of lapis lazuli, these stones are not merely alternatives to diamonds; they are geologically complex masterpieces in their own right. This article will strip away the marketing fluff and explain exactly what these stones are, how we categorize them in the factory, and why they hold such significant value in the B2B supply chain.

We will guide you through the technical distinctions that separate these stones from their “precious” counterparts and reveal the manufacturing realities that dictate their final quality. Whether you are a wholesaler looking to source new inventory or a jewelry designer seeking the perfect medium, understanding the material science behind the stone is the first step toward business success.

Table of Contents

Deconstructing the Terminology: Precious vs. Semi-Precious

The distinction between precious and semi-precious stones is a historical classification that dates back to the mid-19th century, but it remains a dominant force in how we price and process materials today. In the strictest traditional sense, there are only four “Precious” stones: Diamond, Ruby, Sapphire, and Emerald. Everything else—literally every other mineral used in personal adornment—falls under the umbrella of “Semi-Precious.” While this binary system might seem convenient for retail categorization, it is often a source of frustration for geologists and high-end manufacturers because it fails to capture the true value of exceptional specimens.

The “Big Four” vs. The Infinite Variety

In our manufacturing capability at JADE MAGO, we treat the “Big Four” very differently from other materials due to their extreme cost per carat and the specialized machinery required to cut them. However, grouping everything else as “semi-precious” implies a uniformity that simply does not exist. For example, a high-quality piece of Imperial Jadeite (technically semi-precious by Western definition) can fetch millions of dollars, vastly outpricing a low-quality diamond or emerald. This creates a paradox in the industry where the label does not always reflect the price tag.

When we receive orders for processing, we don’t look at the label “semi-precious” to determine the care we take; we look at the rarity and structural integrity of the rough stone. A rare Paraiba Tourmaline or a flawless Black Opal are technically semi-precious, yet they command respect and pricing that rivals the top tier of the gem world. Therefore, when sourcing from Chinese manufacturers, it is vital to understand that “semi-precious” is merely a trade category, not a definitive judgment of quality or beauty.

The Gemological Perspective on Value

From a scientific standpoint, institutions like the Gemological Institute of America (GIA) focus on the specific mineral composition rather than these archaic marketing categories. As manufacturers, we align more with this scientific view because it dictates our production flow. We look at the chemical composition—whether the stone is a silicate, an oxide, or a phosphate—because this tells us how the stone will react to heat, pressure, and polishing compounds.

The value of a semi-precious stone in the manufacturing sector is driven by three key factors: color saturation, clarity, and durability. Unlike diamonds, which have a standardized pricing list, the semi-precious market is wilder and more subjective. A slight variation in the banding of a Malachite or the chatoyancy (cat’s eye effect) in Tiger’s Eye can double the manufacturing cost due to the need for precise orientation during cutting. We teach our apprentices that while the market may call them “semi-precious,” the skill required to unlock their potential is wholly “precious.”

The Geology and Sourcing of Rough Material

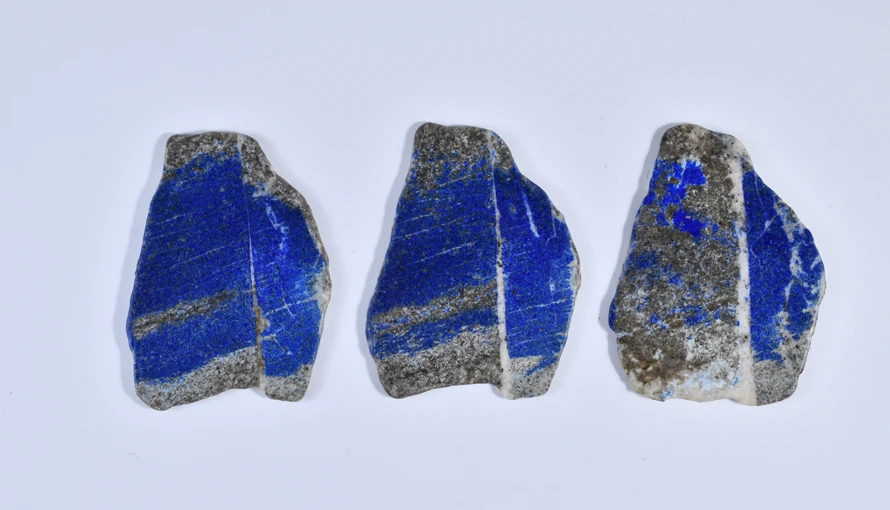

To truly understand these stones, you must understand where they come from and how they arrive at our cutting tables. China has become the global hub for stone processing not just because of labor costs, but because of a deeply established supply chain that aggregates minerals from every continent. We process Lapis from Afghanistan, Agate from Brazil, Turquoise from the United States, and of course, Nephrite Jade from our own domestic mines.

Understanding the Mohs Scale in Manufacturing

The single most important technical metric for any manufacturer is the Mohs Scale of Mineral Hardness. This scale, ranging from 1 (Talc) to 10 (Diamond), dictates exactly which tools we use and the speed at which we can work. Semi-precious stones cover a massive range on this scale, which is why a “one-size-fits-all” factory line does not work in this industry.

For instance, Quartz varieties (like Amethyst and Citrine) sit at a 7 on the Mohs scale. This is the sweet spot for jewelry because it is harder than dust (which is mostly silica, hardness 7), meaning the stone won’t scratch easily with daily wear. Processing quartz requires diamond-tipped tools and specific cooling lubricants to prevent heat fractures. On the other hand, softer stones like Fluorite (hardness 4) or Malachite (hardness 3.5-4) require a much gentler touch. If we ran a piece of Malachite through the same high-speed tumbling process used for Agate, it would disintegrate into powder. This geological diversity means that a factory must possess a wide arsenal of machinery to handle the “semi-precious” category effectively.

The Challenge of Yield and Inclusions

When we buy raw material, we are essentially gambling on what lies beneath the weathered crust of a boulder. “Yield” refers to the percentage of the rough stone that actually makes it into the final product, and for semi-precious stones, this can vary wildly. A ton of raw Rose Quartz might yield 60% usable material, while a high-grade Rhodochrosite might only yield 10% due to its tendency to have structural weaknesses and undesirable inclusions.

Inclusions are materials trapped inside the mineral during its formation. In the diamond world, inclusions are flaws to be eliminated. However, in the semi-precious world, specifically with stones like Rutilated Quartz or Moss Agate, the inclusions are the value. As a processing manager, my job is to visualize the 3D internal structure of the rock before a single cut is made. We must slice the stone in a specific direction to showcase these internal landscapes. This requires a level of artistic intuition that automated machines simply cannot replicate, proving that the processing of these stones is as much an art as it is a manufacturing science.

The Pillars of Chinese Stone Processing

While there are hundreds of mineral varieties that classify as semi-precious, the Chinese manufacturing industry relies heavily on three main families. These specific groups constitute the vast majority of our export volume and require distinct processing lines within our factories. Understanding these “pillars” is essential for any B2B buyer, as they represent the most stable and scalable supply chains in the market.

The Cultural King: Jade (Nephrite and Jadeite)

It would be impossible to discuss the stone industry in China without placing Jade at the very center. At JADE MAGO, this is our heritage and our primary expertise. The term “Jade” actually covers two distinct minerals: Nephrite and Jadeite. While the Western world often categorizes these simply as semi-precious stones, in East Asia, they are revered above diamonds. From a manufacturing perspective, Jade is unique because of its structure. Unlike single crystals such as quartz which can shatter easily, Nephrite is composed of interlocking fibrous crystals.

This felted, interlocking structure gives Nephrite incredible toughness, meaning it is resistant to breaking even if it is not the hardest stone on the Mohs scale. This allows us to carve intricate designs, chains, and hollow bangles that would cause other stones to crumble. When we process high-end Jadeite, we use specialized fluid-cooled saws to prevent any heat damage that might cloud the stone’s translucency. You can read more about the scientific distinction between Jadeite and Nephrite here, but in the factory, the difference is felt in the resistance the stone offers to the grinding wheel.

The Industrial Giant: Agate and Chalcedony

If Jade is the king, then Agate is the soldier of the semi-precious industry. Agate is a form of cryptocrystalline quartz, meaning its crystals are too small to be seen with the naked eye. This material is the backbone of the affordable jewelry market because it is abundant, incredibly durable (Mohs 7), and takes a mirror-like polish with relative ease.

In major processing hubs like Haifeng or Ketang, we process tons of Agate daily. This stone is famous for its natural banding and its ability to absorb dye, which allows manufacturers to create a wide array of colors to match fashion trends. While some purists prefer natural colors, the market demand for uniform red, black (Onyx), or green Agate drives a massive dyeing industry. For a manufacturer, Agate is the perfect training material for new apprentices because it is consistent and forgiving, unlike the temperamental nature of softer stones.

The Energy Market: Quartz and Crystals

The third pillar involves the macro-crystalline Quartz family, which includes Clear Quartz, Amethyst, Citrine, and Rose Quartz. These stones are prized for their clarity and, increasingly, for their perceived metaphysical properties in Western markets. Processing clear crystals presents a specific challenge: visibility of flaws.

When we cut a piece of Amethyst, we are constantly fighting against “color zoning,” which is where the purple color is unevenly distributed within the crystal. A skilled cutter must orient the gemstone so that when you look down through the top (the table), the color appears uniform throughout. Furthermore, Quartz is heat-sensitive. If a technician pushes the polishing wheel too hard and generates too much friction, an Amethyst can turn brown or crack due to thermal shock. Therefore, our crystal processing lines are always flooded with water to keep the stones cool and safe.

Inside the Factory: The Manufacturing Lifecycle

Moving from the raw material to the finished product involves a series of aggressive yet precise steps. To the outsider, a stone factory can look chaotic, but it follows a strict logical flow designed to maximize yield and beauty. The transformation from a rough, dusty rock to a gleaming jewel is a testament to human engineering and patience.

Precision Slicing and Blocking

The first step is always the most nerve-wracking: the initial cut. We use large circular saws with diamond-impregnated blades, ranging from small 10-inch blades to massive 3-meter monsters for giant boulders. The “Blocking” stage is where we cut the stone into manageable cubes or slabs.

This stage requires the most experience because a mistake here is irreversible. The master cutter must read the “grain” of the stone. For example, stones with a chatoyant effect (like Tiger’s Eye or Moonstone) must be cut parallel to the fibrous inclusions. If we cut it perpendicular, the famous “cat’s eye” flash disappears entirely, and the stone becomes lifeless and dull. We often mark the rough stones with waterproof markers to guide the saw operators, ensuring that the best color and pattern are preserved in the center of the slab.

Preforming and Calibration

Once the stone is blocked, it moves to the preforming station. Here, workers use grinding wheels made of silicon carbide or diamond grit to grind away the sharp corners and create the rough shape of the final product. If we are making beads, the cubes are ground into rough spheres; if we are making cabochons (domed stones with a flat back), they are ground into ovals or rounds.

Calibration is critical for the B2B market. Jewelry designers need stones that fit into standard pre-made settings (like 10x14mm ovals or 6mm rounds). We use digital calipers to measure the stones constantly during this process. In the semi-precious industry, a tolerance of +/- 0.2mm is generally acceptable, but for high-end clients, we tighten this to +/- 0.05mm. Achieving this precision requires the stone to be “dopped” (glued) onto a stick so the cutter can manipulate it against the grinding wheel with exact control.

Polishing: The Secret to Valuation

The final stage, and arguably the most important for sales, is polishing. You can have a rare stone with a perfect cut, but if the polish is poor, it will look cheap. Polishing involves moving through a series of progressively finer grits. We might start with a 600-grit wheel to remove deep scratches, move to 1200, then 3000, and finally use a polishing compound like cerium oxide or diamond paste on a felt or leather wheel.

Different stones require different polishing mediums. Jade, for example, loves diamond paste and bamboo wheels, which give it that characteristic “greasy” or oily luster that collectors adore. Quartz, on the other hand, responds best to cerium oxide, which provides a high-gloss, glass-like finish. We inspect the final polish under bright lights to ensure there are no “orange peel” effects (a pitted texture) or lingering scratches. A perfect polish seals the surface of the stone and allows light to enter and reflect back to the eye, unlocking the gem’s true color.

Treatments and Enhancements: What Buyers Must Know

In the world of semi-precious stones, very few materials make it from the mine to the jewelry box without some form of help. “Treatments” are standard industry practices used to improve the durability or appearance of a stone. At JADE MAGO, we believe in full disclosure, as transparency builds long-term trust.

The Role of Stabilization

Some beautiful stones are naturally too soft or brittle to be used in jewelry. A classic example is Turquoise. Natural Turquoise is often chalky and porous; it absorbs skin oils and changes color over time, eventually crumbling. To make it usable, we use a process called “stabilization.”

This involves submerging the stone in a clear epoxy resin under high pressure. The resin penetrates the pores of the stone, hardening it and deepening the color without changing the stone’s fundamental character. This is a widely accepted practice. Without stabilization, 90% of the world’s Turquoise supply would be unusable. Buyers should assume that most soft, opaque semi-precious stones on the market have undergone this process to ensure they survive the manufacturing steps and daily wear.

Heat Treatment and Irradiation

Heat treatment is practically an extension of nature’s own processes. By applying controlled heat to a stone, we can clarify its color or change it entirely. The most common example is turning Amethyst (purple) into Citrine (yellow/orange) by baking it at high temperatures. Similarly, dull blue Aquamarine is often heated to remove green tones and achieve a pure sky-blue hue.

These treatments are permanent and stable. In our supply chain, we distinguish between “Natural Color” and “Enhanced Color.” While enhanced stones are more affordable and uniform, natural untreated stones command a premium for their rarity. It is crucial for buyers to ask their suppliers specifically about treatments, as this significantly affects the valuation of the inventory.

Navigating Quality Control: The Grading Dilemma

One of the most confusing aspects for international buyers sourcing from China is the lack of a universal, standardized grading system for semi-precious stones. unlike diamonds, which have the strict “4Cs” (Cut, Color, Clarity, Carat) regulated by international bodies, the semi-precious market largely relies on individual factory standards. At JADE MAGO, we have established a rigorous internal protocol, but understanding the general market interpretation of grades like A, AB, and B is essential for protecting your investment.

Decoding the Alphabet Grades (A, AB, B)

In the wholesale markets of Guangzhou and Yiwu, you will frequently see stones labeled as Grade A, Grade AB, or Grade B. Generally, Grade A represents the top 10-15% of a production run. These stones display the most vibrant color, possess high translucency (where applicable), and are free from surface defects or visible cracks. When we sort a batch of Amethyst, only the beads with deep, uniform purple and zero visible inclusions make it into the ‘A’ pile.

Grade AB is the commercial standard and usually makes up the bulk of the market. These stones are beautiful and durable but may have slight color variations or minor inclusions that are visible upon close inspection. For most fashion jewelry brands, Grade AB offers the best balance between cost and aesthetic appeal. Grade B, however, is often where disputes arise. These stones usually have noticeable flaws, pale color, or significant mineral inclusions. While they are significantly cheaper, they are often difficult to sell in high-end markets. We always advise our clients to request physical samples of each grade before placing a bulk order, as one factory’s “Grade A” might be another factory’s “Grade AB.”

The Issue of Consistency and Matching

For jewelry manufacturers, consistency is often more important than individual perfection. If you are designing a necklace that requires 50 beads, you need those 50 beads to look identical in color and pattern. This is a massive challenge with semi-precious stones because they are natural materials that vary from vein to vein within the same mine.

To address this, we employ specialized sorting teams whose only job is “color matching.” They work under 5500K daylight-balanced bulbs to group stones into identical batches. A high-quality supplier will never send you a mixed bag of light and dark stones unless “mixed” was the specific requirement. When evaluating a supplier, checking their ability to provide consistent “strands” or “lots” over a long period is far more critical than checking the quality of a single sample stone.

The Future of Stone Manufacturing

The stone processing industry is not static; it is currently undergoing a significant transformation driven by technology and ethical concerns. As manufacturers, we are seeing a shift away from the wild, unregulated mining practices of the past toward a more sustainable and traceable future.

Sustainability and Ethical Sourcing

Modern consumers are increasingly asking, “Where did this stone come from?” This pressure is felt all the way back to the factory floor. China has implemented stricter environmental regulations regarding dust control and water waste management in processing zones. This means that factories like ours have invested heavily in water filtration systems to recycle the thousands of liters of water used daily for cutting and polishing.

Furthermore, “Ethical Mining” is becoming a key keyword in B2B negotiations. We are seeing a rising demand for stones that can be traced back to specific, conflict-free mines. While the semi-precious supply chain is complex and often fragmented, the industry is slowly moving toward blockchain-based tracking solutions that verify the journey of a stone from the rough boulder to the finished polished cabochon.

The Rise of “Perfectly Imperfect”

Interestingly, while technology allows us to cut cleaner and more perfect stones, the fashion trend is moving in the opposite direction. We are receiving more orders for “organic” cuts—stones that retain their natural, rough edges or feature heavy inclusions. Designers are embracing the “wabi-sabi” aesthetic, finding beauty in the natural flaws of the material.

This trend is excellent for the industry because it utilizes material that would have previously been discarded as waste. Stones like “Salt and Pepper” Diamonds or heavy-inclusion Moss Agate are now commanding high prices. This shift forces us to retrain our cutters to exercise restraint; instead of grinding a stone into a perfect oval, they must now carefully polish the natural contours of the rock, preserving its geological history.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are semi-precious stones “real” stones?

Yes, absolutely. The term “semi-precious” is a classification of value and rarity, not a description of authenticity. These are natural minerals mined from the earth, just like diamonds or rubies. However, buyers should always be wary of synthetic or imitation stones (like glass or plastic) being sold under gemstone names. Always verify the material with a trusted manufacturer.

Which semi-precious stone is the most expensive?

While prices fluctuate, Paraiba Tourmaline is currently one of the most expensive semi-precious stones, often costing more per carat than high-quality diamonds due to its neon-blue color and extreme scarcity. Other high-value contenders include Alexandrite (known for changing color) and high-grade Tanzanite. In the context of the Chinese market, top-tier Imperial Jadeite remains the undisputed king of value.

Do semi-precious stones fade over time?

Most stones are stable, but some can fade if exposed to direct sunlight for prolonged periods. Amethyst and Rose Quartz, for example, are photosensitive and can lose their color intensity if left in the sun. Treated stones, particularly dyed Agates, may also fade if the dye is not sealed properly. We recommend storing all gemstone jewelry in a dark, cool place when not in use.

What is the “Marble Trap” in stone sourcing?

This is a critical warning for all B2B buyers. The “Marble Trap” refers to the common practice of selling dyed Marble or Calcite as high-value semi-precious stones. Geologically, Marble is a soft rock (Mohs hardness of 3-4), whereas stones like Jade or Agate are much harder (Mohs 6-7). Because Marble is porous and absorbs dye exceptionally well, unscrupulous sellers often dye white marble green to sell as “New Jade” or “Malaysia Jade,” or dye it blue to mimic Lapis Lazuli or Turquoise.

From a manufacturing perspective, these materials are easy to spot: a steel knife will easily scratch marble, but it will slide off real Jade or Agate. Furthermore, Marble is sensitive to acid; a drop of mild acid will cause it to fizz and dissolve, damaging the polish. While dyed marble can be a valid, low-cost material for costume jewelry, buying it under the false impression that it is a durable semi-precious stone is a costly mistake. Always check the hardness and ask for the specific mineral name, not just the trade name.

-900x375.webp)