Introduction

“Natural jade” means the stone formed through natural geological processes. It may be cut, carved, drilled, or polished, because these are form processing steps that do not change the material’s natural origin; however, the stone’s treatment status must be disclosed separately in B2B trade.

If you only remember one rule, remember this: Natural ≠ Untreated. In real trade, the highest-risk problems come from missing or unclear disclosure, not from the existence of treatment itself.

Table of Contents

Why Buyers Keep Arguing About “Natural”

In B2B procurement, “natural” often gets used as a marketing shortcut, but your contract needs it as a technical classification. The most common dispute pattern is simple: the buyer thinks “natural” implies “no treatment,” while the seller means “not synthetic,” and both feel misled when the product arrives.

This confusion gets expensive because it turns into chargebacks, platform complaints, and brand trust damage—especially for cross-border buyers who must defend product claims in multiple markets. The fix is not more adjectives; the fix is a two-part statement: (1) natural origin, and (2) treatment status (untreated / treated with disclosure).

The Fast Definition Buyers Can Use in Contracts

The Simple Rule—Origin vs Intervention

Use “natural” only to describe origin. Then treat everything humans do to the stone as either form processing (allowed without changing natural status) or treatment (material-altering, must be disclosed).

This is why cutting, drilling, and polishing are not “disqualifying.” They change shape and surface finish, not the underlying geological origin or the stone’s internal chemistry/structure.

The B2B Disclosure Standard (Minimum Acceptable)

A professional purchase order should not stop at “natural jade.” It should specify one of these: Natural, untreated; Natural, treated (treatment disclosed); or Synthetic / man-made (and never described as natural).

This standard matches how serious labs and trade references frame gemstone terminology and disclosure, and it also aligns with the direction of consumer-protection guidance that discourages misleading claims. For U.S. selling contexts, the FTC Jewelry Guides emphasize avoiding deceptive claims and discuss disclosure expectations for treatments that affect value or care requirements.

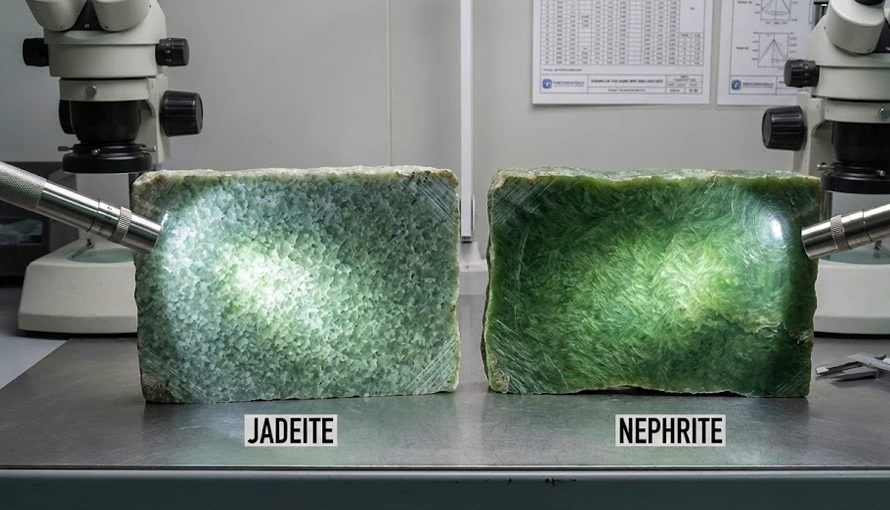

“Jade” Isn’t One Stone—Jadeite vs Nephrite (Why It Matters)

Two Materials, One Market Word

In global trade, “jade” is used as an umbrella term, but it commonly refers to two different materials: jadeite and nephrite. If your PO doesn’t specify which one you are buying, you are creating room for misunderstanding on price, durability expectations, and appearance range.

This matters in B2B because your product page might say “jade,” but your returns department will react very differently if the buyer expected jadeite and received nephrite (or received a look-alike). Tight language here is cheaper than after-sales conflict.

Procurement Implications You Can Actually Use

Jadeite and nephrite behave differently in processing and finishing, and that affects feasibility, scrap risk, and unit economics in manufacturing. Material structure and directional behavior can change how force travels through the stone during cutting and carving, so “same design” does not guarantee “same result” across different jade types or even across different pieces of the same type.

If you are sourcing for consistent SKU-level output, your spec should include a realistic tolerance range and an acceptance policy. Professional factories manage ranges, not absolutes, because process consistency does not equal product consistency when the raw material itself varies internally.

Natural vs Untreated vs Treated vs Synthetic (Stop the Confusion)

The Four Buckets Buyers Must Separate

A practical procurement framework uses four categories. First is natural & untreated, meaning natural origin and no material-altering treatment; second is natural & treated, meaning natural origin but intervention altered internal structure/chemistry/stability and therefore must be disclosed; third is synthetic, meaning lab-created; and fourth is imitation, meaning a different material made to look similar.

This is the core idea buyers miss: a treated stone can still be of natural geological origin, and treatment is not the same thing as “synthetic.” The commercial risk comes from non-disclosure, because it creates compliance and trust failure even when the product is otherwise wearable or attractive.

Why “Natural” Without Disclosure Is Incomplete Information

In trade practice, “natural” is still used to distinguish from synthetic materials, but it does not finish the job. Without the treatment statement, your description is incomplete and can be interpreted in the most unfavorable way during disputes.

If you sell cross-border, incomplete wording is also a platform risk. The cleanest path is to standardize your product language so that “natural” never appears alone; it always appears with “untreated” or “treated (with disclosed method).”

What Counts as Treatment (Material-Altering)—and Why Buyers Care

The Technical Definition Buyers Should Enforce

A stone is classified as treated when it originates from a natural source but undergoes human intervention that alters internal structure, chemical composition, color stability, or long-term physical behavior. If a process affects only shape or surface finish, it is not treatment; if it alters internal structure or chemistry, it is treatment.

This definition is procurement-friendly because it avoids endless argument about whether a treatment is “minor.” The rule is simple: material state change qualifies as treatment regardless of degree, so the right commercial action is disclosure, not debate.

Common Treatments (Disclosure Required)

Common treatment methods that should be treated as disclosure-level information include dyeing, polymer impregnation/resin filling, stabilization treatment, structural heat treatment, and chemical soaking or enhancement. These are not inherently “bad,” but they are contract-level facts because they can affect stability, care requirements, and resale claims.

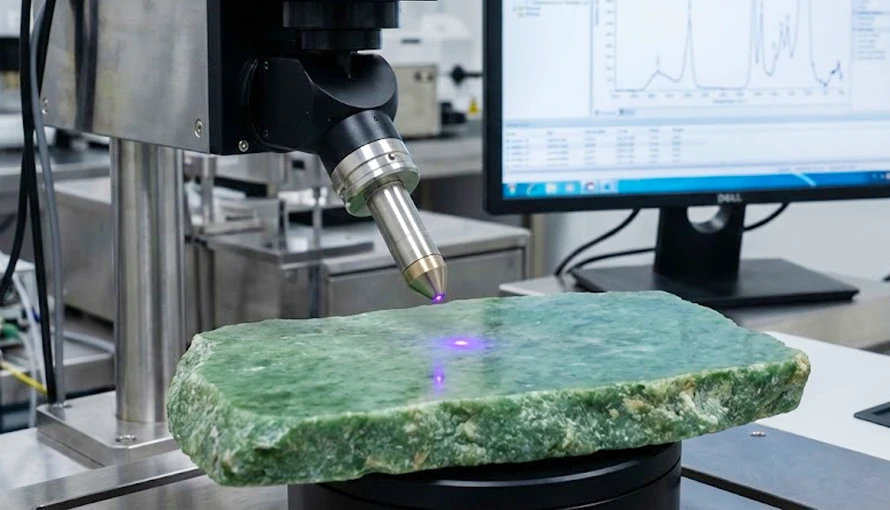

In jadeite specifically, polymer impregnation (often discussed in the trade as “B jade”) has long been documented and can be detected via appropriate methods such as infrared spectroscopy in lab contexts. Buyers should reference reputable gemological education sources when setting internal policy, rather than relying on marketplace rumors.

What Does NOT Change “Natural” Status (Crafting & Manufacturing)

Cutting, Drilling, Polishing, Carving—Still Natural

Form processing includes cutting, carving, drilling, polishing, and shape/size modification, and these steps do not affect natural classification because they do not change internal chemistry/structure. This is the key sentence to use when a customer asks whether carving “makes it not natural.”

The practical takeaway is that a finished product can be fully manufactured (CNC or hand) and still be “natural,” provided the underlying material remains untreated. Your disclosure should separate “how it was made” from “what the stone is.”

CNC vs Hand Carving—Why This Confuses Buyers

Buyers often assume CNC equals “better” and hand equals “imprecise,” but natural stone does not behave like metal or plastic. CNC carving prioritizes dimensional accuracy and repeatability, while hand carving adapts in real time to material variability; neither is universally superior, and suitability depends on material and design.

This matters for “natural jade” conversations because a buyer may confuse breakage or variation with “treatment” or “fake.” A more accurate explanation is that natural material variability can reveal hidden defects during processing, and manufacturing choices change the risk profile rather than changing the stone’s origin.

The Manufacturing Reality Behind “Natural” (Why Breakage Happens)

What Jade Mago clarifies upfront: Many fractures exist below the visible surface and may remain dormant until cutting, carving, vibration, or thermal stress exposes them. Fracture exposure is often a material reality—not automatically a processing error—so we build risk checkpoints and acceptance ranges into the workflow and quotation logic.

Hidden Fractures Are Real, and They Can Be Invisible Pre-Processing

Many fractures exist below the visible surface, and they may not affect appearance or integrity until the material is stressed. Cutting, carving, and polishing introduce stress that can expose fractures, and non-destructive testing has practical limits in routine production—so fracture exposure is a material reality, not automatically a processing error.

This is why a buyer may feel something “changed,” even though the stone was always the same. Processing often reveals what was already there, especially when vibration, thermal gradients, and stress redistribution occur as material is removed.

Why “Almost Finished” Pieces Sometimes Fail

Before machining, internal forces can be balanced and cracks can remain dormant, so the stone looks stable. As the part gets thinner in late-stage processing, stress concentrates and previously compressed defects can become critical, making failure look sudden even though it is cumulative.

This reality matters for B2B expectations. If your contract demands zero breakage or identical results, it is misaligned with natural stone physics, and it will create structural disputes no matter which factory you choose.

How Buyers Can Verify “Natural Jade” Without Becoming Gemologists

Step 1 — Require a Supplier Disclosure Sheet (Before You Ask for Reports)

Start by requiring a written disclosure that separates: material identity, natural origin claim, treatment status, and any special care requirements. This forces clarity early and prevents the common “natural-only” ambiguity that causes disputes later.

If you want a procurement-friendly template, structure it as fields rather than prose. Fields reduce interpretation risk, and they make it easier to compare multiple suppliers objectively.

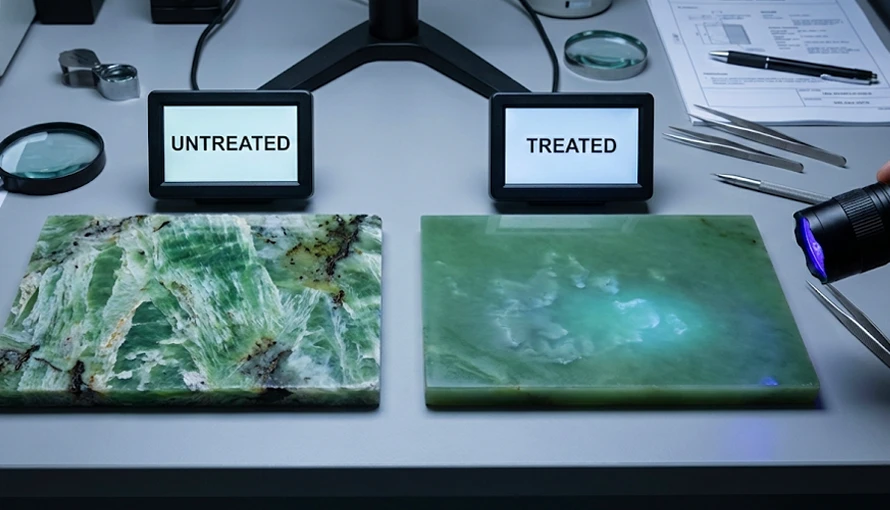

Step 2 — Use Visual Screening as Risk Triage, Not “Proof”

Visual screening can help you triage risk, but it cannot conclusively prove authenticity. Treat appearance as a probability signal: extreme uniformity across multiple pieces can be a warning sign, but the only correct conclusion from appearance is “low-risk” or “high-risk,” not “treated” or “untreated.”

This is where many buyers accidentally overclaim and then get trapped by their own words. If commercial stakes are high, escalation should be to verification, not to confident labeling.

Step 3 — Choose Testing Strategically (Risk-Driven, Not Emotion-Driven)

Not every transaction requires laboratory testing, and more testing does not automatically reduce disputes. Testing should be risk-driven, and lab reports should support honest disclosure rather than replacing it.

A practical matrix is to align tests with the risk question. For example, FTIR is commonly used where polymer filling is suspected, while Raman is useful for mineral identity doubts, and combined testing can broaden coverage when suspicion is mixed.

How to Communicate Lab Results (So Reports Don’t Backfire)

Report Scope Beats Report Volume

Buyers often say “the report proves it’s untreated,” but that language is risky because it treats detection limits as certainty. A safer approach is to state what was tested, what was detected, what remains untested or uncertain, and to align wording with disclosure standards.

This prevents “report cherry-picking” and reduces liability created by over-promising. It also keeps your internal compliance team aligned with what the lab actually did, not what you wish the lab proved.

Avoid Absolute Phrases in Marketing and Contracts

Avoid phrases like “fully certified,” “guaranteed untreated,” or “proven natural in all aspects.” Those claims expand expectations beyond the report’s scope and can increase disputes rather than reducing them.

If you sell in the U.S., this discipline also fits the spirit of FTC guidance that aims to prevent deceptive claims in jewelry marketing, including around treatments and material representations.

Copy-Paste Supplier Questions (Procurement Checklist)

Material Identity (Stop “Jade-Like” Ambiguity)

Ask the supplier to state whether the material is jadeite or nephrite, and to confirm it is not an imitation material being described as “jade.” Require the answer in writing, because vague terms like “jade-like” or “stone material” create high-risk misrepresentation scenarios in B2B trade.

If the supplier cannot state the material identity clearly, treat that as a qualification failure. This step saves more money than any inspection performed after mass production.

Treatment Disclosure (The Non-Negotiable)

Ask: “Has the stone undergone any intervention that alters internal structure, chemistry, color stability, or long-term behavior?” Then ask them to name the method if yes, because “industry standard so no need to disclose” is not a valid technical argument.

If you need third-party testing, align it with the exact risk you are trying to manage. Don’t accept random certificates as proof of everything, because mismatched testing creates false confidence.

Manufacturing + QC (Align Expectations With Natural Material Reality)

Ask the supplier how they manage variability: orientation planning, conservative vs aggressive parameters, and inspection checkpoints. Then ask for an acceptance policy that uses tolerance ranges rather than absolute promises, because “same file, same result” is a myth in natural stone manufacturing.

This prevents the most common post-delivery argument: “Why isn’t every piece identical?” A professional answer is probabilistic and range-based, not defensive and absolute.

Glossary + Buyer-Safe Wording (Use This in Listings and POs)

Glossary (Short, Operational Definitions)

“Natural” means geological origin, not “unprocessed,” and it should not be used alone in B2B trade. “Treated” means intervention that alters internal structure/chemistry/stability, and it requires disclosure even if the seller calls it “minor.”

“Synthetic” means lab-created, and it cannot be described as natural. “Imitation” means a different material made to resemble jade, and it must not be represented as jade even if the look is similar.

Approved Phrases vs Risky Phrases

Use language that separates origin and treatment. A buyer-safe pattern is: “Natural [jadeite/nephrite], untreated” or “Natural [jadeite/nephrite], treated (method disclosed),” because it makes your claim testable and contract-compatible.

Avoid “100% natural” without a treatment statement, and avoid absolute promises like “fully certified” or “guaranteed untreated.” Those phrases increase disputes because they imply certainty beyond what trade practice and testing can support.

Conversion Modules (B2B Inquiry Ready)

If you want to standardize supplier communication, build one internal rule: no PO line item is approved unless it includes both “natural origin” and “treatment status.” That one rule eliminates most “natural jade” arguments before production starts.

If you’re sourcing custom carving (CNC or hand), align design tolerance and acceptance ranges upfront. Professional process selection is a risk-management decision, not a style preference, and it should be treated as part of your procurement specification.

About Jade Mago (B2B): We help brands and studios turn natural jade and other semi-precious stones into production-ready parts through a process-first manufacturing approach. Our work focuses on choosing the right carving strategy—CNC precision carving, hand carving, or hybrid workflows—based on material variability, yield risk, and tolerance requirements.

FAQ

Does carving or polishing make jade “not natural”?

No, carving and polishing are form processing steps that do not change natural status, because they change shape and surface finish rather than internal chemistry or structure. The “natural” question must be answered separately from the “treated or untreated” question.

Can jade be natural and still treated?

Yes, a treated stone can still be of natural geological origin. The key requirement in B2B trade is that treatment status is disclosed clearly, because undisclosed treatment is the highest risk scenario.

If a lab report exists, can I say “guaranteed untreated”?

That wording is risky because reports have scope and detection limits, and they do not cover everything. Use report-aligned language that states what was tested and what was detected, and avoid absolute claims like “guaranteed untreated.”

Why do “same designs” produce different outcomes in natural jade?

Natural stone variability dominates outcomes, so identical processes do not guarantee identical results. CNC can reduce variance but cannot eliminate it, and professional factories manage ranges rather than absolutes.

How do I reduce disputes if I’m selling into the U.S. market?

Use clear material descriptions and disclose treatments that affect value or care, and avoid deceptive or implied claims. The FTC Jewelry Guides are a key reference point for how U.S. regulators view misleading jewelry marketing statements.

-900x375.webp)