“Low-cost jade processing” sounds like an efficiency story, but in B2B it is usually a risk story. Two suppliers can quote the same CAD file and still deliver radically different outcomes, because natural stone does not behave like standardized industrial materials. If you only compare unit price, you often end up buying someone else’s uncertainty.

This article explains the technical and commercial logic behind low-cost quotes—what’s legitimately efficient, what’s silently risky, and how to structure your sourcing so “cheap” doesn’t become expensive later. It’s written for buyers who need repeatable decisions: studio owners, product managers, and procurement teams who want stable delivery, defensible disclosure, and fewer disputes.

Table of Contents

The Buyer’s Trap: When “Cheap” Really Means “Risk Shifted”

A low quote is not automatically a red flag, and a high quote is not automatically better. What matters is where the variability and liability end up once the order enters production. In natural stone manufacturing, you can standardize the process, but you cannot standardize the stone, so outcomes are probabilistic even with consistent settings.

The 3 cost myths procurement repeats (and why they fail)

The first myth is “same design, same result.” CAD/CAM assumes homogeneous material, but natural stone violates that assumption, which is why “same file, same result” is a repeated source of conflict. A supplier quoting aggressively may be pricing as if the stone behaves like a standardized polymer, which it does not.

The second myth is “photos prove grade.” Treatments and surface enhancements are often designed to look good under common lighting, and visual “perfection” can be statistically more suspicious than imperfection in many natural stones. If you treat visuals as proof, you unintentionally incentivize appearance-first shortcuts.

The third myth is “low quote equals factory efficiency.” True efficiency exists, but price drops are frequently created by skipping checkpoints, tightening parameters beyond safe yield, or using vague disclosure language that shifts liability to the buyer. When that happens, your “savings” reappear as scrap, delays, customer complaints, or chargebacks.

The three ways risk gets shifted to the buyer

Material risk shows up as unseen fractures, density variation, and structural randomness. Many fractures have no surface expression, so they cannot be reliably detected by routine pre-inspection; processing stress simply reveals what was already there.

Process risk shows up as chipping, subsurface damage, sudden breakage, and poor polish response. CNC can be highly repeatable, but it is less tolerant of hidden defects because it cannot adapt in real time the way a skilled hand process can.

Disclosure risk shows up as “unknown status,” inconsistent terminology, and overconfident claims. The biggest disputes are rarely about whether a piece is pretty; they’re about whether the seller’s wording implied a certainty that the evidence never supported.

Definitions That Prevent Disputes: Processing vs Treatment vs Enhancement

Before you talk price, you need shared language. In B2B, the most expensive misunderstandings are definitional: a buyer hears “natural” and assumes “untreated,” while a supplier means “not synthetic.” The only sustainable approach is to define terms first and align claims to what can actually be supported.(jadeite vs nephrite)

What counts as “processing” in manufacturing terms

Processing is what a factory does to shape the material into your product: cutting, carving, drilling, grinding, polishing, and assembly. These actions change geometry and surface condition, but they do not inherently imply chemical or internal modification. Processing is normal manufacturing, and it is where most cost differences originate.

In practice, the same processing action can produce different outcomes depending on the stone’s internal structure. That is why buyers should treat “processing difficulty” as a real cost driver, not as a negotiator’s excuse.

What counts as “treatment/enhancement” in trade terms

Treatments are interventions that alter internal voids, color behavior, stability, or surface characteristics beyond ordinary machining. Examples include polymer impregnation/resin filling, dyeing, heat treatment, and some surface coatings. These interventions are not automatically “bad,” but they are commercially meaningful and therefore require consistent disclosure in professional trade.(GIA)

The buyer’s practical concern is not moral purity. The concern is whether the product’s durability, repairability, long-term appearance, and resale/compliance claims match what the material can actually deliver.

The disclosure language buyers should standardize (contract-grade)

Your purchase order should standardize a small set of terms and forbid improvisation. Use phrases such as “untreated,” “treated,” “polymer impregnated / resin filled,” “dyed,” “heat treated,” and “status undetermined,” and require that any claim be paired with “testing scope” when relevant. This is not bureaucracy; it’s a dispute prevention system.

Avoid absolute language like “fully certified” or “guaranteed untreated” unless you also define the sampling plan, methods, and limitations. Overconfident wording expands liability beyond the evidence, which is why it increases disputes instead of reducing them.

The Real Engineering Economics Behind “Low Cost”

Low-cost, when legitimate, is usually created by controlling yield and variance. In stone processing, efficiency is not only speed; it is the ability to reduce catastrophic failure and keep outcomes inside an agreed variation range.

Cost driver tree: what actually decides unit price

Unit price is shaped by five linked variables: raw material selection window, expected yield, cycle time, finishing labor, and QC intensity. If any one of these is priced unrealistically low, it typically reappears as a failure mode later.

Yield is the hidden giant. A quote that assumes “near-metal-like predictability” will be cheaper, but it will also be brittle: when internal defects surface, losses become binary pass/fail, especially in pure CNC workflows. A quote that assumes real-world stone behavior may look more expensive upfront, but it can be cheaper in total landed cost because it budgets for variance management instead of pretending variance doesn’t exist.

Why jade is not “like metal” in CNC terms

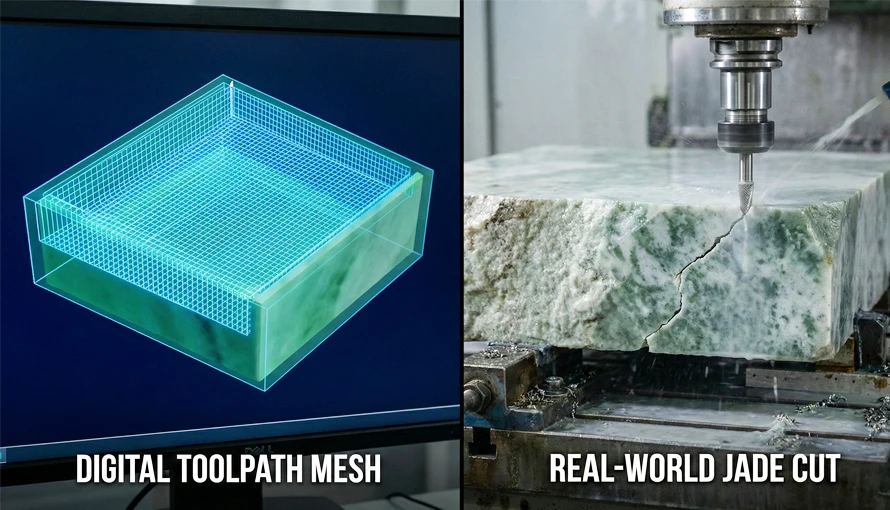

CNC is powerful, but it is rigid. It runs fixed parameters and toolpaths, so it cannot “feel” resistance changes the way hand carving can. When stone is heterogeneous, CNC can expose hidden cracks abruptly, and the failure often looks sudden to a buyer even though the fracture existed already.

This is why professional factories treat process selection as risk management, not as a style preference. CNC is ideal for tight tolerance and repeatability, but hand carving or hybrid workflows are often more stable when defect risk is high.

The hidden cost curve: cheaper quote → higher QC + rework + returns

A supplier can lower the quote by pushing aggressive parameters, skipping mid-process checks, or narrowing disclosure. Those moves reduce apparent cost at the quoting stage, but they tend to increase real cost after production begins, because variability doesn’t disappear—it just changes who pays for it.

The most reliable low-cost suppliers are not the fastest. They are the suppliers who reduce catastrophic breakage and stabilize delivery by using conservative strategies when uncertainty is high, and automation when predictability is high.

The “Low-Cost Risk Pathways” That Create Expensive Disputes

When a “cheap” order turns into a conflict, it usually followed one of a few predictable pathways. Knowing these pathways lets you audit a quote before you approve it.

Pathway A: Aggressive machining to reduce cycle time

Toolpath strategy often matters more than machine brand. Cutting direction, entry/exit, depth progression, and how load is distributed over time can amplify or reduce fracture risk, because stress follows toolpath geometry rather than your design geometry.

Aggressive feed rates and deep passes reduce cycle time but amplify hidden defects and increase binary failures. Conservative strategies trade speed for yield stability, which is often the correct trade when you’re buying natural stone at scale.

Pathway B: “No disclosure problem” becomes “disclosure problem later”

Some suppliers treat disclosure as a marketing obstacle instead of a trade obligation. They use vague terms, avoid documenting uncertainty, or imply conclusions without evidence. The conflict appears later when your customer asks direct questions, or when a platform/compliance request forces you to state the treatment status precisely.

The defensible rule is simple: what is documented is defensible; what is assumed is not. A supplier who refuses to document uncertainty is not reducing risk—they are delaying it.

Pathway C: Appearance-first shortcuts and surface-driven selling

Treatments and surface enhancements can produce high visual appeal quickly. That is why appearance alone is insufficient for a trade conclusion, and why overly uniform visual consistency can be a risk signal rather than a comfort signal.

Your sourcing protocol should separate “cosmetic appeal” from “material truth.” That separation is a business function, not a gemology hobby.

Pathway D: Under-specified acceptance criteria

If your spec does not define acceptable variation, your delivery becomes an argument about taste. Natural stone demands ranges: acceptable variation range, marginal range, and failure range, with agreed tolerances and examples.

The cheapest dispute is the one you prevent at PO stage. A clear spec sheet and acceptance criteria can eliminate most post-delivery conflict without needing any lab test.

Verification Protocol: What Buyers Can Check Before Paying

Verification does not mean “prove perfection.” In trade, verification means reducing uncertainty to a level that matches the commercial risk and the promises you intend to make.

Tier 1: Visual screening + process evidence (fast screen)

Visual screening is a risk filter, not a verdict. Your goal is to identify high-risk signals, document them, and decide whether to escalate. Natural stones show irregularity, while artificial interventions tend to appear repetitive, overly uniform, or concentrated along cracks and fissures.

Process evidence matters because it reveals whether the supplier is managing uncertainty or hiding it. Ask for batch IDs, in-process photos at defined checkpoints, and clear, consistent explanations that separate fact from interpretation.

Tier 2: Manufacturing QC checks (factory-side)

QC in stone manufacturing must be designed around failure modes. Mid-process inspection checkpoints are especially valuable because hidden fractures often reveal themselves only after stress is introduced, not before processing starts.

Hybrid workflows formalize this logic. They automate what is predictable, and reserve human judgment for what is not, using risk checkpoints between stages to prevent small defects from becoming catastrophic failures.

Tier 3: When to escalate to lab testing (and what it can’t prove)

Lab testing is a decision tool, not a marketing stamp. A risk-driven strategy is often more effective than blanket testing, and misaligned testing can increase disputes by creating false confidence.

FTIR is highly effective for detecting polymers and resins, which makes it well-suited to screening for polymer impregnation/resin filling. However, FTIR detects what is present, not everything that may have happened, and “FTIR negative” does not equal “untreated.”

Because every method has limitations, test communication must always include three statements: what was tested, what was detected, and what remains untested or uncertain. That language keeps your claims aligned with the evidence and prevents accidental overpromising.

Contract + Spec Sheet: The Documentation That Prevents Most Supplier Conflicts

If your goal is stable low-cost sourcing, the contract is not a legal afterthought. It is the control plane that turns variability into a managed range.

The minimum spec sheet fields for jade processing orders

A practical B2B spec sheet should define: material window (type and allowed variation), design constraints (minimum thickness, hole diameter, edge radius), tolerance plan (critical vs cosmetic dimensions), finish standard (polish level and allowable pits), and disclosure requirements.

You should also define sampling logic for acceptance checks. Even a simple “pre-production sample → mid-production checkpoint → pre-shipment inspection pack” workflow can sharply reduce surprises, because it makes the factory show you reality early rather than explaining it late.

Acceptance criteria that reduce argument space

Acceptance criteria work best when they are visual and threshold-based. Define what counts as a crack vs a surface line, define maximum chip size by location, and define color deviation boundaries relative to an approved master sample.

This approach is consistent with how professional factories handle natural variability: they manage ranges and probabilities, not absolutes. Over-promising consistency creates structural disputes, so your acceptance system should be built around realistic variation bands.

Payment + sampling + dispute workflow

For low-cost sourcing, align payment stages to risk reduction. Use a small deposit to start, then release additional payment after pre-production sample approval and a mid-production checkpoint. If a dispute occurs, use a remedy ladder (rework → partial credit → remake) that is written before emotions enter the conversation.

When uncertainty exists, escalation options include laboratory testing, third-party verification, or enhanced disclosure with limitation notes. Refusing escalation is often framed as confidence, but unmanaged certainty is what produces larger conflicts later.

What Legit Low-Cost Looks Like

The market has two kinds of “low cost.” One is engineered efficiency. The other is hidden risk.

Efficiency signals (good cheap)

Legit low cost often comes from better yield planning, better process strategy, and better batching. Hybrid workflows can reduce catastrophic breakage and stabilize delivery by combining CNC roughing with manual finishing at high-uncertainty points, which improves average yield and lowers scrap compared with pure CNC on heterogeneous stone.

Legit low cost also comes from clear communication. A supplier who documents what they observed, what they controlled, and what remains uncertain is typically safer than a supplier who promises perfection with no supporting process evidence.

Risk signals (bad cheap)

Risky low cost tends to include vague disclosure, refusal to show process checkpoints, and overconfident claims about treatment status. It also tends to include pricing that ignores variance: tight tolerances with no yield premium, or “identical outcome” promises for a material that cannot support zero variance.

From a technical perspective, some unpredictability is irreducible. That reality cannot be negotiated away, only managed with process design and contracts.

A 12-question supplier interview script (copy/paste for procurement)

Ask four questions about process, four about QC, and four about disclosure/testing. For process, focus on whether the supplier shifts attention from machine brand to strategy and risk trade-offs, because outcomes are driven by toolpath and parameter logic more than marketing claims.

For QC and disclosure, focus on whether the supplier can explain limitations without defensiveness. A supplier who can say “here’s what we know, here’s what we don’t, here’s what we will document” is often the one who prevents disputes.

Jade Mago Approach: Cost Transparency Without Disclosure Ambiguity

Jade Mago’s positioning is not “cheapest possible.” It is risk-clarified manufacturing: explain process logic, document checkpoints, and align disclosure to evidence rather than to sales pressure. This approach follows a core principle: technical truth over marketing language, and disclosure before conclusion.

Our baseline promises (what we will document)

We focus on traceability and process evidence, because it helps buyers manage commercial risk without relying on mystical claims or unrealistic guarantees. We document checkpoints that are meaningful in natural stone production, especially around stages where hidden fractures are likely to reveal themselves under stress.

We also encourage contract language that matches reality. If you want tighter tolerances, we will treat that as a yield-and-risk decision rather than a simple “yes/no” capability statement.

What we will not promise (to keep your claims defensible)

We do not use lab reports as marketing guarantees. Reports support disclosure; they do not replace it, and more testing does not automatically mean less risk if it creates unrealistic expectations or expands liability beyond test scope.

We avoid absolute claims like “guaranteed untreated” unless the testing scope, sampling plan, and interpretation limits are explicitly defined. That stance protects your downstream brand claims and keeps your customer-facing language consistent with what is actually defensible.

CTA by buyer type

If you’re a studio owner or founder, send your CAD and target cost. We’ll propose design-for-yield edits that reduce breakage risk while preserving the visual intent, because the cheapest part is usually the part you don’t have to remake.

If you’re a brand or procurement team, request a spec sheet template and a sampling/checkpoint workflow. Your fastest win is to standardize definitions and acceptance criteria before you scale volume.

Quick Summary: A Buyer’s Decision Framework

If you only do five things, do these. First, define processing vs treatment terms at PO stage so “natural” doesn’t get interpreted three different ways later. Second, lock a spec sheet with tolerance and acceptance criteria because natural stone requires ranges, not absolutes.

Third, require traceability evidence and checkpoint documentation because hidden fractures often only reveal themselves during processing stress. Fourth, use tiered verification and escalate to testing only when it matches the commercial risk, remembering that FTIR and other tools are filters, not verdicts. Fifth, document the dispute workflow before payment, because what you agree on calmly is what saves you when delivery pressure rises.

FAQ

What does “low-cost jade processing” actually mean in manufacturing terms?

In real production, “low-cost” usually means the supplier is optimizing yield, cycle time, tooling life, and rework rate—not simply charging less margin. The risk is that some suppliers reduce price by skipping QC gates, pushing aggressive CNC parameters, or using vague disclosure, which shifts cost to the buyer later.

Is “processing” the same as “treatment”?

No. Processing refers to cutting, carving, drilling, grinding, polishing, and assembly—manufacturing steps that shape the stone. Treatment/enhancement refers to interventions that alter internal voids, stability, or color behavior (e.g., polymer impregnation/resin filling, dyeing, heat/bleaching, coatings). The business risk is usually non-disclosure, not the existence of treatment itself.

Does “natural jade” automatically mean “untreated”?

Not automatically. In trade practice, “natural” may be used to mean “not synthetic,” but that doesn’t always clarify whether the piece is treated. If you need “untreated,” put it as a defined term in your PO/spec, and tie it to documentation and testing scope where relevant.

-900x375.webp)